Member of both the Pro Football Hall of Fame and College Football Hall of Fame, baseball all-star, the first president of the NFL, 2x Olympic gold medalist, the most versatile modern-day athlete, a man with a town named after him, professional actor, and Akapamata (“caregiver”). Jim Thorpe was an amazing athlete with a lot of natural talent who wore a lot of hats. However, in part because of his Native American Heritage, Thorpe suffered much adversity. Despite the discrimination and marginalization, and a very rough childhood, Jim Thorpe beat the odds and became one of the greatest athletes of all time.

Jim Thorpe, baptized “Jacobus Franciscus Thorpe” in the Catholic Church and given the native name, Wa-Tho-Huk, or “Bright Path,” was born and raised in the Native American Sac and Fox Nation, what was called “Indian Territory” (now Oklahoma). Thorpe was born without a birth certificate, and his United States citizenship was under question. The United States government did not consider Native Americans natural-born citizens until June 2, 1924, when President Calvin Coolidge signed the Indian Citizenship Act into law. The exact date of his birth is scrutinized, but Thorpe stated that he was born May 28, 1888, “near and south of Bellemont – Pottawatomie County – along the banks of the North Fork River,” despite his baptismal certificate being listed as May 22, 1887, which many biographers believe to be the date of his birth. Thorpe was raised as a Sac and Fox and was a practicing Roman Catholic, just like his parents.

It is important to note that at the time, there was severe racial inequality within the United States. Americanization policies, which took place from the late 19th century and the early 20th century, intended to irradicate Native American culture. The federal government believed that if Native Americans were able to assimilate into Western culture, it would ease racial tension. They therefore outlawed religious and traditional practices of Native American Nations and required children to attend schools in which they were forced to speak English, attend Christian church, and leave their traditions behind. This is likely why Thorpe was a baptized Catholic, as were his parents, despite their Native American heritage.

Jim Thorpe’s childhood was filled with significant loss. He was born a twin, but his brother, Charlie, tragically died of pneumonia at the age of nine. Thorpe began having problems in school following his brother’s death and ran away several times. Because of his troubles in school, his father sent him off to the Native American boarding school, the Haskell Institute, in Lawrence, Kansas. As a small child sent away from his family, Thorpe was left to grieve his brother’s death alone. Two years later, tragedy struck again, and his mother died from complications related to childbirth. His relationship was rocky with his father after this, and Thorpe struggled with depression. He then left home to work on a ranch. He returned home at sixteen, where Thorpe attended Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. A few months later, he became an orphan at the age of 16 when his father died of gangrene. He again dropped out of school and resumed working on a ranch.

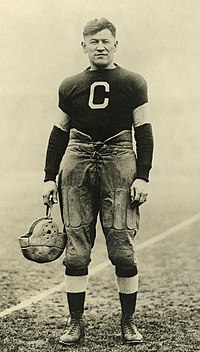

Despite these hardships, Thorpe was determined to attend college and reenrolled a few years later. Many say that Thorpe was a natural-born athlete. He rarely practiced and yet managed to succeed at just about anything he set his mind to. In 1907, before he began this athletic career, he was walking past the track and field team and decided he might as well give it a try. He leaped 5 foot, 9 inches in the high jump (in his street clothes, mind you. This was completely unplanned), beating all the track and field athletes at his school. If that wasn’t impressive enough, he picked up football, baseball, lacrosse, and ballroom dancing (and won the 1912 intercollegiate ballroom dancing championships). Initially, his track and field coach tried to persuade Thorpe not to play football because he feared he would be injured if tackled.

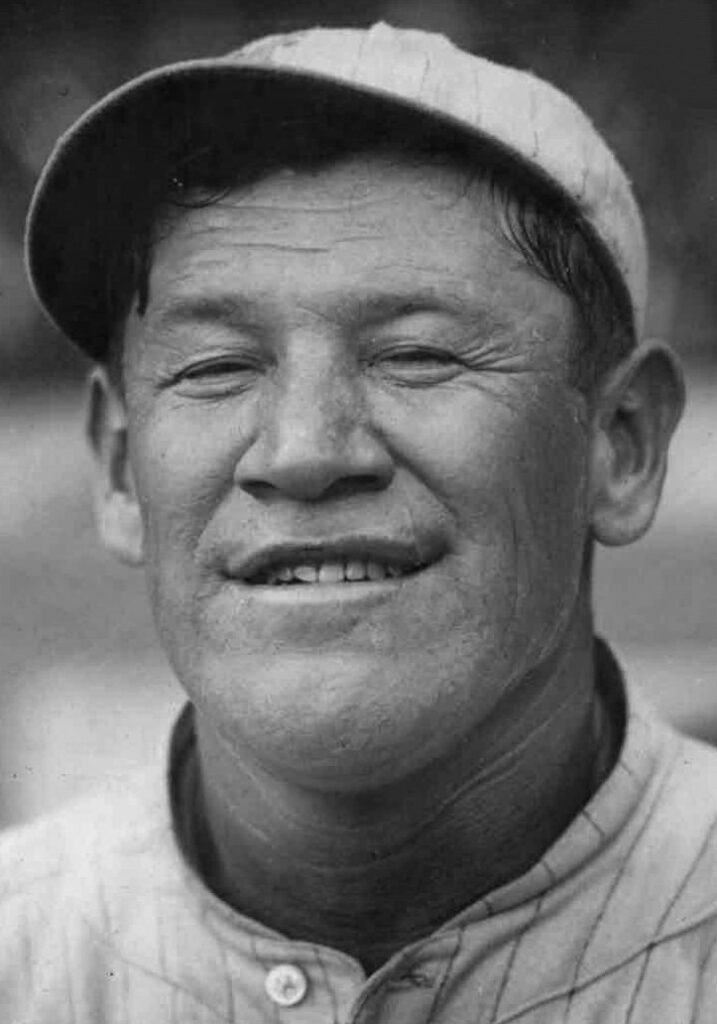

That fear was unfounded, however, as no one could catch him to tackle him. His team beat Harvad, where he scored every point in the game, and his football fame rose. Even President Eisenhower said, “Here and there, there are some people who are supremely endowed. My memory goes back to Jim Thorpe. He never practiced in his life, and he could do anything better than any other football player I ever saw.” Thorpe became third-team All-American in 1908 and a first-team All-American in 1911 and 1912. Thorpe also played semi-professional baseball in the Eastern Carolina League for Rocky Mount, North Carolina, in 1909 and 1910. Although he was paid, he only received about $35 a week. It was common at the time for college players to play professional baseball during the summer to earn some cash, but most used aliases. Thorpe did not.

Throughout his college career, Jim Thorpe experiences the effects of racism due to his Native American heritage. To advertise for games, his school named the football team The Indians, and journalists often portrayed games as conflicts of Native Americans against the dominant racial group, white people. In fact, the first time Thorpe appeared in The New York Times, the headline read “Indian Thorpe in Olympiad; Redskin from Carlisle Will Strive for Place on American Team.” His accomplishments were regularly described in racial contexts, although it had no bearing on his athletic ability.

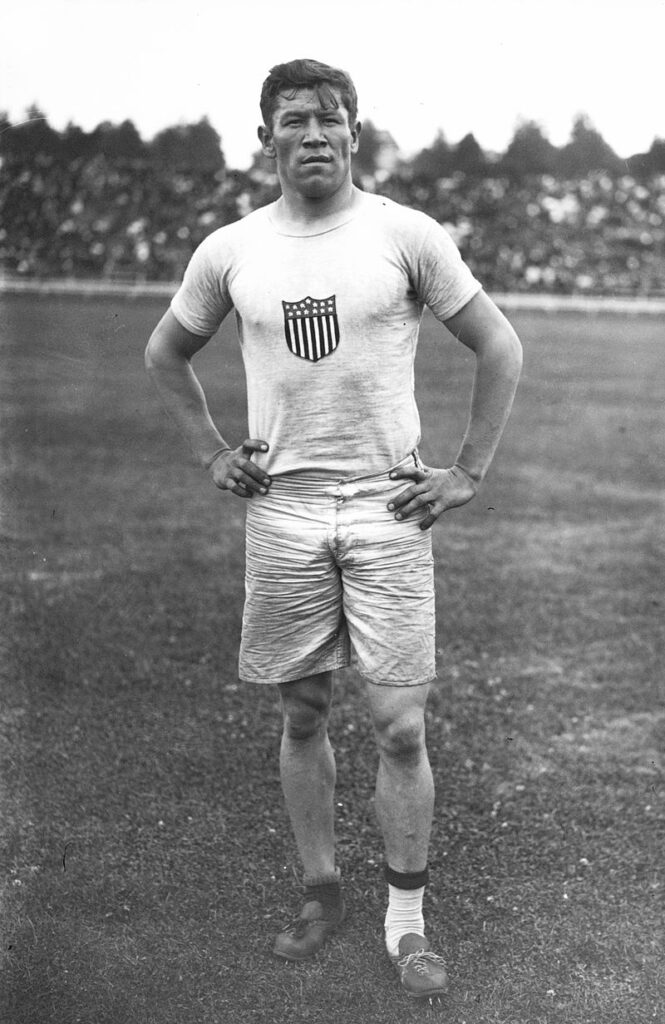

Although he did little training or practice for football or track and field, he did train for the Olympics, starting in the spring of 1912 for the Summer 1912 Olympics, held in Sweden. Most athletes train for the Olympics much longer, but Thorpe did not need to because of his natural ability. In 1912, Thorpe entered the Olympics for both the pentathlon and the decathlon, newly introduced in 1912, and competed in the long jump and high jump. During his first competition, the pentathlon, he won four out of five events, earning him the gold medal. Later that day, he tied for fourth in the high jump and placed seventh in the long jump. Thorpe’s first and only decathlon was next. He was expected to lose but beat the competition by 688 points (wearing a mismatched pair of shoes from the dumpster because someone stole his), and his record of 8,413 remained for almost two decades. Thorpe won the gold medal. Thorpe also played in an exhibition baseball game, which featured two teams composed mainly of U.S. track and field athletes.

The medals were presented to the athletes, and life seemed to be really coming together for Thorpe. Back home, Thorpe was the star attraction in a parade on Broadway. A humble man who did not like being the center of attention, he recounted, “I heard people yelling my name, and I couldn’t realize how one fellow could have so many friends.” He then competed in the Amateur Athletic Union’s All-Around Championship, winning seven of the ten events and came in second in the other three with a total point score of 7,476 points, beating the previous record.

In 1913, things went sour for Jim Thorpe. Although the public did not care that he had played baseball semi-professionally briefly before entering the Olympics, the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) did. In 1912, there were strict rules regarding who could qualify for the Olympics, and professional players were not allowed to participate. Because he had played semi-professionally, the Amateur Athletic Union argued that Thorpe should have been disqualified and, therefore, lost his Olympic medals, titles, and awards. They then retroactively disqualified him. Despite his performance at the 1912 Olympics, Thorpe now had all of his accomplishments stripped away.

While it was true that Thorpe had played semi-professionally for money, the AAU broke their own rules for disqualification when they stripped Thorpe of his Olympic success. Technically, they only had 30 days from the closing ceremonies of the Olympics to retroactively disqualify Thorpe. The AAU did not take action until roughly six months later, well outside of the timeframe they were required to take action. That did not matter, it seemed, despite protests from Thorpe. This is again where Thorpe experiences discrimination due to being Native American.

Jim Thorpe did not quit. His new title of “professional athlete” garnered him attention from professional sports clubs. He went on to play pro football and semi-pro baseball. He also toured with the “World Famous Indians” during his off-season, although he had little experience with basketball. His football career is impressive. He played for the Bulldogs, one of fourteen teams to form the American Professional Football Association (two years later named the NFL), of which Thorpe was their first president. He played football until age 41, which was pretty much unheard of at the time, considering the many positions he played on the team.

He then went on to become an actor. He sold the rights to his life story to MGM, and they made a movie about Thorpe. They also cast him in his first acting role, Chief Black Crow, in “Battling with Buffalo Bill” in 1931. What followed was a pretty successful acting career. He was in more than 70 movies, mostly Westerns, where he played either a Native American or an athlete. His final role was in the 1950 John Ford classic, Wagon Master, in which he played a Navajo.

Universal Studios was the first to hire him, casting him as Chief Black Crow in Battling with Buffalo Bill in 1931. Soon, MGM hired him for a baseball film. Later came a football picture with his old coach, Glenn Scobie “Pop” Warner.

Perhaps Jim Thorpe’s greatest legacy? How much he gave back to his community. Despite the adversity he faced in relation to his ethnicity, he never stepped away. During the Great Depression, he constantly helped Native Americans find jobs, often in the film industry. He also co-founded the Indian Center where Native people from all over the United States flocked to and called their “home away from home.” Thorpe and his grandmother were their welcome wagon.

The Indian Center was later named the Native American Actors Guild, helping hundreds of Native people secure TV and cinema jobs. He wanted to make sure there was Native American representation on the big screen, and he wanted to make sure that Native Americans were hired to do it. Thorpe’s son, Richard, said, “In those days, dad was always helping others financially or by finding them work in the movies. He never uttered a bad word about anyone. He was a very warm person. Many times he would take me with him, and I got to see the look of compassion on my father’s face and the looks of gratitude and the tears of thanksgiving on the faces of the people he helped…especially the children. I was very proud of him and loved him very much! Plus, he let me ride in the rumble seat of his Model A.” He personally helped countless people who needed food or shelter and was a major resource for his community. This is why he was given the name “Akapamata,” meaning “Caregiver” in Sac & Fox.

There is a happy end to Thorpe’s Olympic tale. In 1983, the AAU withdrew his professional status prior to the Olympic games in 1912. This meant that his medals, titles, and awards were reinstated. However, Jim Thorpe did not live to see it happen. Thirty years after his death, his children accepted replicas of medals and awards. His original medals, which had hung in a museum, had been stolen. What has not been stolen, however, is Jim Thorpe’s legacy of resilience and strength in the face of adversity.